The art of illustration. Illustration as a field of art Illustration in European culture is a faithful companion of the written word – first on parchment, then on paper. The word itself comes from the Latin verb illustro – to visualise, enlighten, clarify – and sounds similar in all languages influenced by Latin. Techniques for its production and perpetuation have changed – from woodcut, lithography, photomechanical techniques, such as rotogravure, offset and blueprint, to digital printing. The function remains the same: to depict what is described, to tell a story with an image, to express an idea. Over time, illustration gained autonomy in the art world and is now a field in its own right.

Historical beginnings of illustration

Book and press illustration thrived in the 19th century with the spread of printing. Polish illustrated periodicals drew patterns from Western Europe, many of which used the same root word in their titled: ‘Illustrated London News’ in London, ‘L’Illustration’ in Paris, ‘Illustrierte Zeitung’ in Leipzig or ‘La Ilustración’ in Madrid. The best-known national magazines of this period – i.e., ‘Tygodnik Ilustrowany’, ‘Kłosy’, ‘Wędrowiec’ and later ‘Nowości Ilustrowane’ – published literary, cultural, social, historical and natural-science content, accompanied by illustrations made by professional cartoonists, well-known artists and painters such as Chełmoński, Matejko and the Gierymski brothers. The function of the graphics accompanying the texts was to present the content or a work of art itself. Text has been illustrated since the turn of the 20th century. One of the first illustrators was Stanisław Wyspiański, whose works were printed in ‘Rocznik Krakowski’. An exceptional illustrated magazine was the Warsaw ‘Chimera’ with covers by Ferdynand Ruszczyc. The development of book and press illustrations is closely related to the development of editing and printing techniques. Over time, it would stand as a commentary on the information, and an interpretation of the piece, as well as a medium of its own history.

Book and press illustration thrived in the 19th century with the spread of printing. Polish illustrated periodicals drew patterns from Western Europe, many of which used the same root word in their titled: ‘Illustrated London News’ in London, ‘L’Illustration’ in Paris, ‘Illustrierte Zeitung’ in Leipzig or ‘La Ilustración’ in Madrid. The best-known national magazines of this period – i.e., ‘Tygodnik Ilustrowany’, ‘Kłosy’, ‘Wędrowiec’ and later ‘Nowości Ilustrowane’ – published literary, cultural, social, historical and natural-science content, accompanied by illustrations made by professional cartoonists, well-known artists and painters such as Chełmoński, Matejko and the Gierymski brothers. The function of the graphics accompanying the texts was to present the content or a work of art itself. Text has been illustrated since the turn of the 20th century. One of the first illustrators was Stanisław Wyspiański, whose works were printed in ‘Rocznik Krakowski’. An exceptional illustrated magazine was the Warsaw ‘Chimera’ with covers by Ferdynand Ruszczyc. The development of book and press illustrations is closely related to the development of editing and printing techniques. Over time, it would stand as a commentary on the information, and an interpretation of the piece, as well as a medium of its own history. In the 1950s, in the twilight of Stalinism, when Poland experienced an artistic thaw, a space was created for artists who manifested independence from political ideologies and created modern works of art. This marks the beginning of what is referred to as the Polish School of Illustration, which also rapidly gained recognition abroad. Outstanding works by Józef Wilkoń, Zbigniew Rychlicki, Bogdan Butenko, Jerzy Flisak, Anna Gosławska-Lipińska, Gwidon Miklaszewski, Andrzej Czeczot, Zbigniew Lengren and Edward Lutczyn not only won prizes at international competitions and triumphed on foreign markets, but also shaped the imagination of several generations of children as well as adults. For the majority, the master was Jan Marcin Szancer (born in 1902, died in 1972), whose works became part of the canon of art for children, especially those accompanying the works of Jan Brzechwa.

Book illustration

Educated in the tradition of Young Poland, Szancer presented the world in children’s books in a realistic but gentle manner. The work of other illustrators was influenced by various phenomena and trends in art. Book illustrations by Zbigniew Rychlicki, the first Pole to receive the prestigious, international Hans Christian Andersen Award, and the creators of Miś Uszatek [En: Teddy Drop Ear], refer to folk culture. The works of Józef Wilkoń, who illustrated over 200 books for children and adults, make reference to the work of Marc Chagall. The characters, mainly animals, presented by Wilkoń illustrate not only the narrative structure of the work, but also the character traits and mental states of the characters. Bogdan Butenko, although he started out in Szancer’s studio, developed a set of aesthetics described as avant-garde and used comedy – for example, in books about the adventures of Gucio and Cezar or Kwapiszon. Olga Siemaszko, the creator of some wonderful illustrations for ‘Alice in Wonderland’ and ‘The Adventures of Tom Thumb’, although traditionally educated, referred to cubism and futurism in her works and was therefore able to create fantasy worlds that developed the readers’ imagination.

Illustration in the press

Reproductions and drawings accompanying journalistic texts tend to serve as a commentary on content or current events. Satirical cartoon stories became the hallmark of publications such as ‘Szpilki’ featuring the work of Jerzy Flisak and Anna Gosławska-Lipińska or ‘Przekrój’ with Professor Filutek by Zbigniew Lengren, and press illustrations are still a popular component of magazines to this day. Andrzej Czeczot, who made his debut in the weekly ‘Szpilki’, published his works in foreign satirical magazines – for example, in the German ‘Pardon’, the ‘New York Times’ and ‘New Yorker’ – and after returning from abroad he drew for ‘Polityka’. Edward Lutczyn also started out at ‘Szpilki’ and his famous caricatures and satirical drawings were printed in ‘Gazeta Wyborcza’, ‘Playboy’ and ‘Przekrój’.

It’s impossible to see everything, but this world is worth exploring

Book illustration is doing great, despite the widespread digitisation of the media. Good books for children are brought out by publishing houses that specialise in this field – such as Bajka, Nasza Księgarnia, Egmont or Adamada – and these include ones illustrated by Adam Pękalski. Contemporary Polish illustrators are among the world leaders in this art, which – according to Jadwiga Okrassa, an author of press illustrations and graphics – complements, explains, ennobles or simply embellishes literary, press and documentary publications. It provokes, evokes emotions, and creates the little idiosyncrasies of this world.

A beautiful tribute to Polish children’s illustration is the book Admirals of the Imagination. 100 years of Polish Illustration in Children’s Books, issued by the Dwie Siostry publishing house in 2020. You can learn more about illustration as a world art in the book ‘The Illustration Handbook: A Guide to the World’s Greatest Illustrators Illustrations’ by Nick and Tessa Souter (Muza 2012).

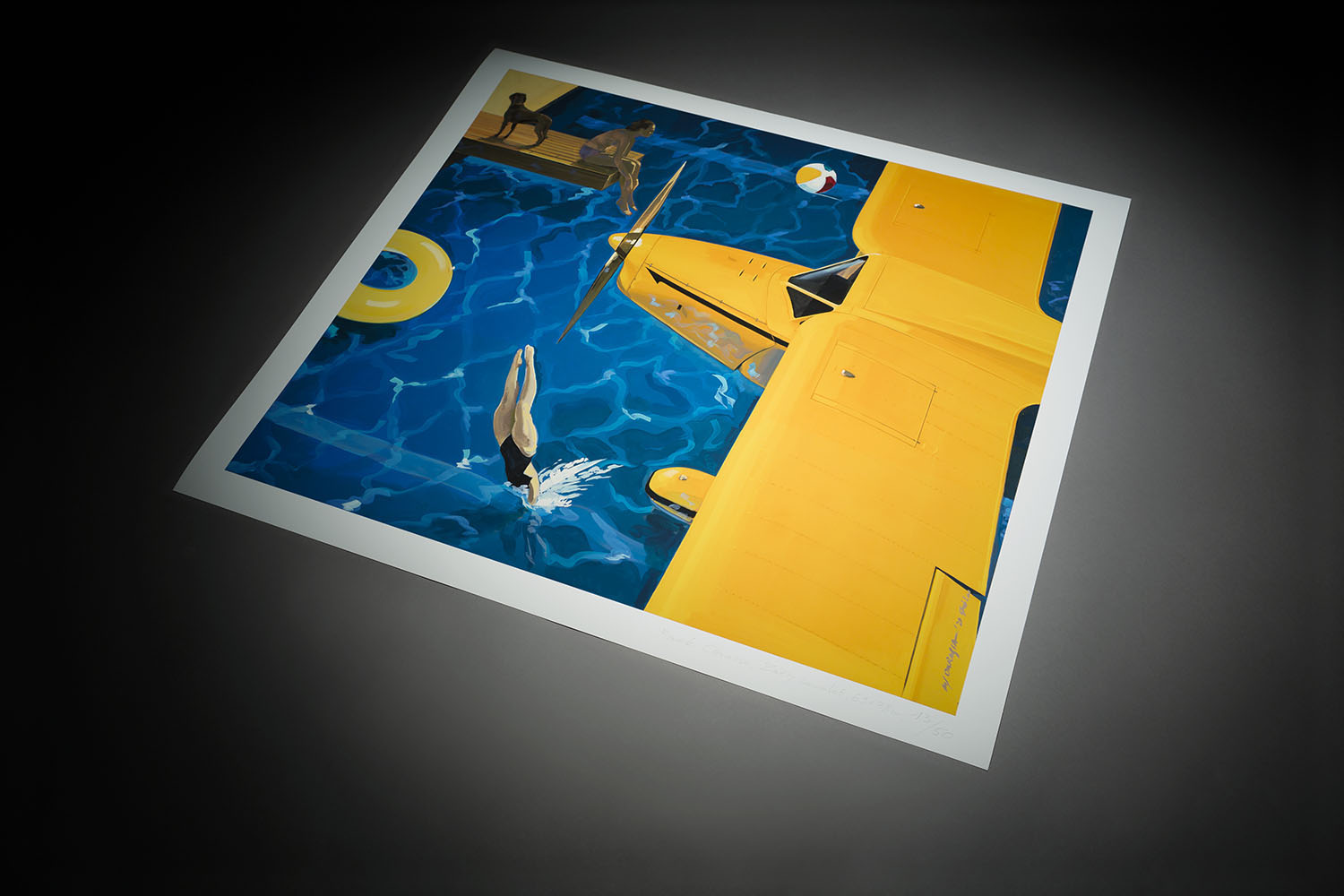

Header illustration: Jadwiga Okrassa, Rembrandt’s Cat, crayon, pencil, paper 30×40 cm